My Chinese-born daughter has been cast as an orphan in a school production of “Annie.” She sings the songs until they are constantly cycling through my head. “No one cares for you a smidge when you’re in an orphanage,” she sings. “Empty belly life. Dirty smelly life.”

The other members of the orphan troupe were never orphans. They’re just playing them on stage. And of course, “Annie” is a 1930s period piece based on a comic strip with cartoonish, larger-than-life heroes, buffoonish villains, and fun, catchy songs– far removed from the Chinese orphanage where my daughter once lived.

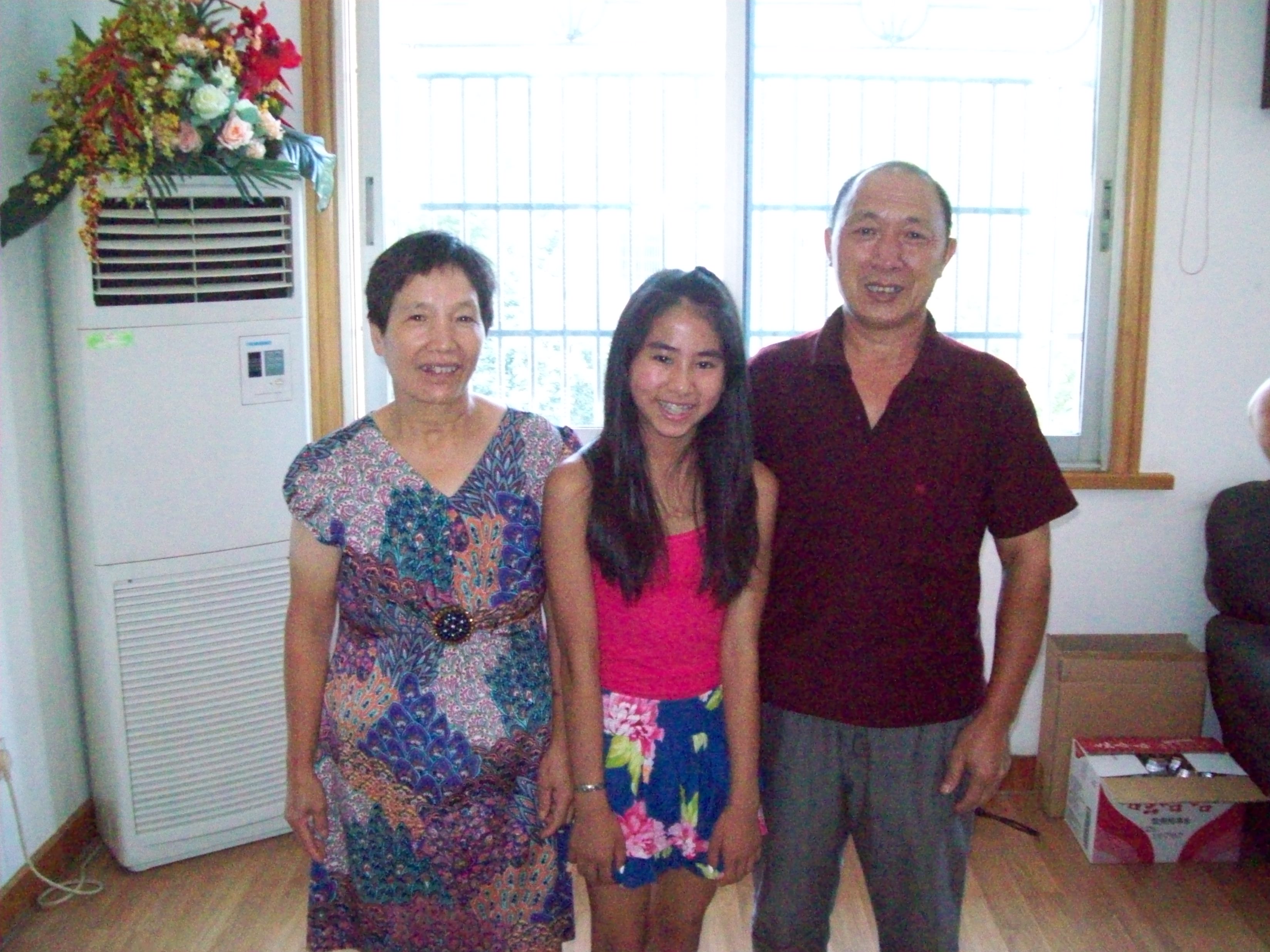

We’ve been back there twice. The first time, the babies were squirmy and curious. They reached for us and other visitors and nibbled on our fingers. Their heads swiveled as we carried them around as if it were rare and wondrous to see the world from a vantage point other than a crib.

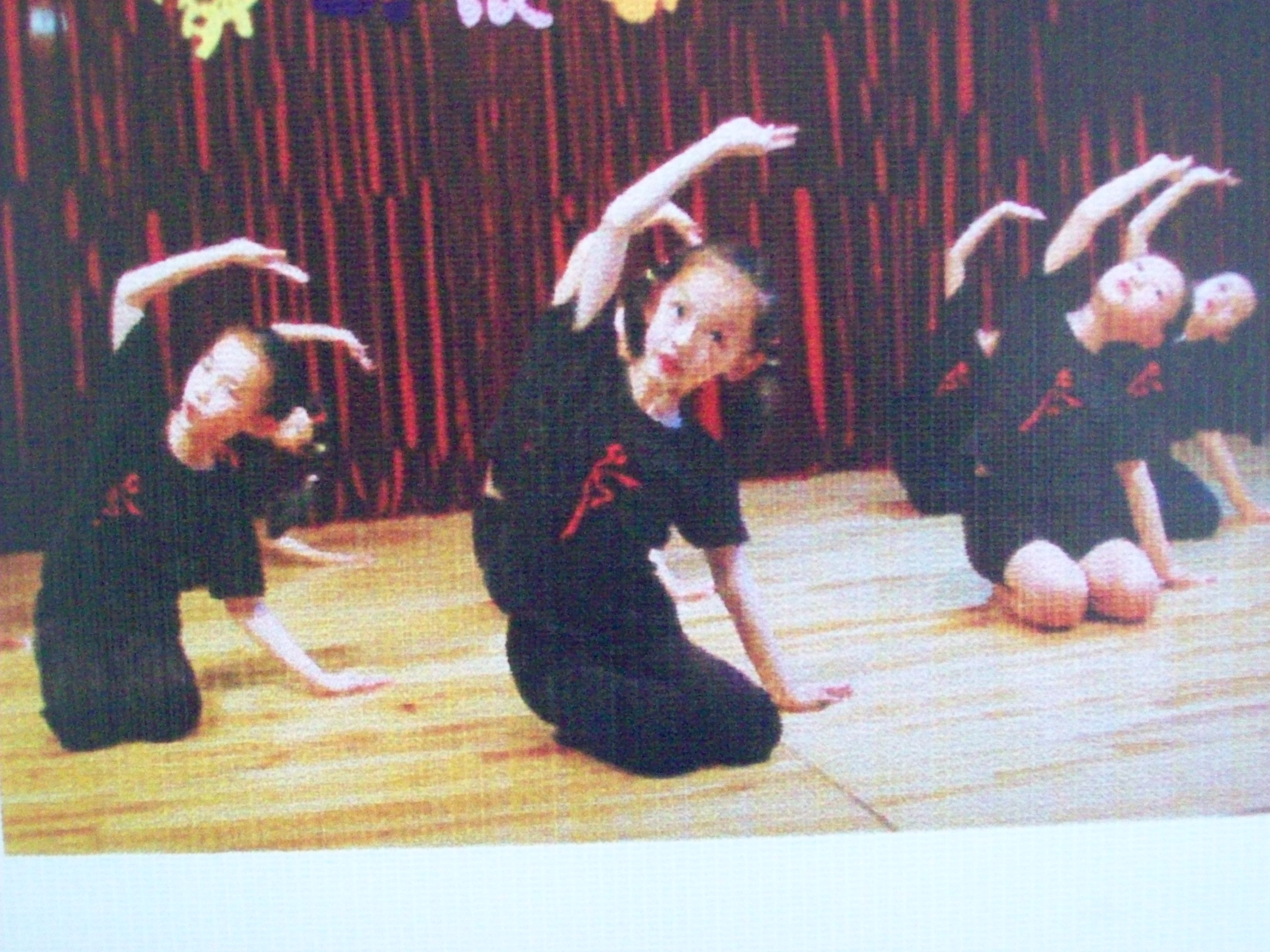

In the three-year gap between our visits, with an increase in domestic adoption and healthy children being sent to foster care in the countryside, the children who remained at the orphanage mostly had disabilities. Babies who were blind or had albinism or cleft palates wanted to be picked up but then went limp because they didn’t know how to be held. They grabbed for me and called me “Mama.” In the playroom, older children lined up in chairs, rising from their seats to sway to an episode of ”Teletubbies,” the closest thing we saw to a plucky song and dance routine.

Lines like “empty belly lives, dirty smelly lives” make me cringe. I’m afraid of simplistic views of difficult circumstances and strained resources and caretakers who are stretched thin and cultural differences, like the lack of mattresses in cribs, that westerners can easily interpret as deprivation.

“Don’t it seem like the wind is always howling?” my daughter sings. “Don’t it seem like there’s never any light?” “Annie” is a rags-to-riches fantasy about exploitation and rescue: the kind of narrative so embedded in our own culture that we sometimes don’t see all the complications of judging another culture according to our own or thinking that the solution to the vast need at a real orphanage is easier than it is.

As my daughter sings “Hard Knock Life,” I’m reminded of the importance of homeland visits– of taking children back to witness where they came from so they can understand that “dirty and smelly” are often cultural constructs and that you can usually find people who care more than a smidge but are often faced with seemingly insurmountable obstacles.

The real children in a real orphanage continue to haunt me. But I’m grateful that we’ve had opportunities to go back. Because of that, I can let my daughter just enjoy the play, trusting that she knows the difference between the complexities of real life and a fun musical with a happy ending.